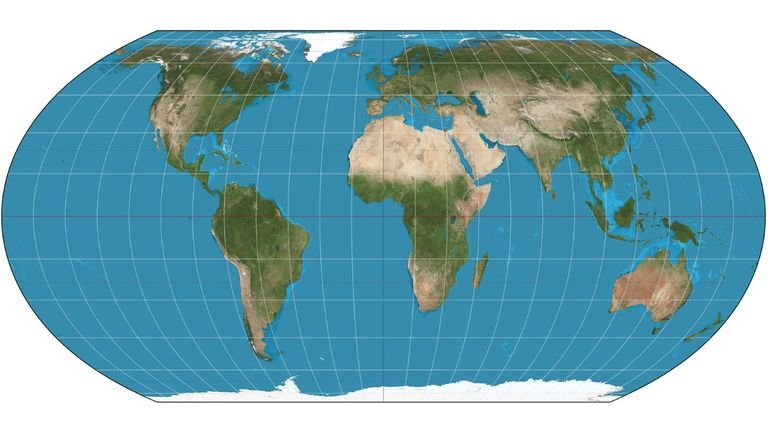

For decades, schoolchildren across Africa have stared at classroom walls decorated with a world map that tells a subtle but powerful lie. On that map—the centuries-old Mercator projection—Africa looks smaller, almost overshadowed by Europe and North America. Greenland, a frosty island with fewer than 60,000 people, seems to rival Africa in size, when in reality Africa is about 14 times larger.

This distortion is not an innocent accident. The Mercator projection, drawn in 1569 by Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator, was originally created to help European sailors navigate the seas. Its straight lines made sea routes easier to plot, but the price was the warping of continents’ sizes, especially those close to the equator. Over time, that warped vision of the world seeped into textbooks, classrooms, and even people’s imagination of Africa’s place in the world.

Now, the African Union (AU), together with advocacy groups like Africa No Filter and Speak Up Africa, is saying: enough is enough. In August 2025, the AU formally endorsed a campaign urging the world to move away from the Mercator projection and adopt a fairer alternative—the Equal Earth projection. For the AU, this is not about maps alone; it is about dignity, identity, and reclaiming Africa’s rightful size on the world stage.

Table of Contents

The Map That Served Sailors but Failed Students

The Mercator map was a technological breakthrough in the 16th century. Its grid made compass bearings easy, so sailors could chart long voyages without the mathematical headaches of curved lines. But for everyday use, especially in classrooms, it is deeply misleading.

By stretching landmasses further from the equator, Mercator makes northern regions—Europe, Russia, Canada—look much larger than they are, while Africa, South America, and parts of Asia look shrunken. For example, Canada appears to cover more land than Africa, when in truth Africa is three times larger.

The result is not just geographical confusion but also psychological damage. As economist Rabah Arezki once argued, this distortion helped fuel colonial arrogance, portraying Africa as a “small, conquerable space” during the scramble for Africa in the 19th century. The AU now believes that continuing to use this projection feeds a lingering sense of marginalisation.

Children in African classrooms grow up seeing their continent minimised on the map. “It might seem to be just a map, but in reality, it is not,” said Selma Malika Haddadi, deputy chairperson of the AU Commission. Maps influence perception, and perception shapes confidence, diplomacy, and power.

A Campaign for Equal Earth

To change the narrative, the AU is backing the “Correct the Map” campaign, spearheaded by Africa No Filter and Speak Up Africa. Their proposal is to replace Mercator with the Equal Earth projection, introduced in 2018. Unlike Mercator, Equal Earth preserves relative land sizes more accurately while still keeping a familiar, globe-like shape.

This matters not just for geography but also for culture and identity. Fara Ndiaye, co-founder of Speak Up Africa, explained that distorted maps harm African children’s self-worth. If a child grows up believing Africa is small, they may unconsciously accept the idea of Africa being less important. The campaign therefore calls for African schools to adopt Equal Earth in classrooms so that students see the continent’s true scale from the start.

The Equal Earth projection also offers a symbolic victory. It rejects the ideology of power embedded in Mercator. By shifting the lens, Africans can literally see themselves bigger, prouder, and more central.

Taking the Fight to the World

The AU’s push is not just an African affair. Leaders want Equal Earth to become the default map in global institutions like the United Nations, World Bank, and international schools. Already, the World Bank says it is phasing out Mercator in its web products, using Equal Earth or Winkel-Tripel instead.

The AU has also forwarded its request to the UN Committee of Experts on Global Geospatial Information Management (UN-GGIM), which will review it formally. Meanwhile, regional blocs like CARICOM in the Caribbean have joined the call, describing Equal Earth as a way of rejecting centuries of “power and dominance” embedded in the Mercator worldview.

The road ahead will not be easy. The Mercator map is deeply entrenched, not only in textbooks but also in software, media, and even people’s mental maps of the world. Changing it will take political will, public campaigns, and a re-education process across continents. But for Africa, this is a fight worth waging.

By championing Equal Earth, the AU is not just correcting geography—it is demanding recognition. As the campaign slogan insists: correcting the map means correcting the narrative.

More Than a Map

The push to ditch the Mercator map is, at its heart, about respect. Africa is the second-largest continent on Earth, rich in land, people, and resources. Yet for centuries, its image has been diminished on a sheet of paper. That skewed picture has influenced how others see Africa—and how Africans see themselves.

By endorsing the Equal Earth projection, the AU hopes to reset that perception, teaching the next generation of African children that their continent is not small or marginal but vast and central. In doing so, Africa is sending a message to the world: maps are not neutral; they tell stories. And Africa is ready to tell its own.

Join Our Social Media Channels:

WhatsApp: NaijaEyes

Facebook: NaijaEyes

Twitter: NaijaEyes

Instagram: NaijaEyes

TikTok: NaijaEyes