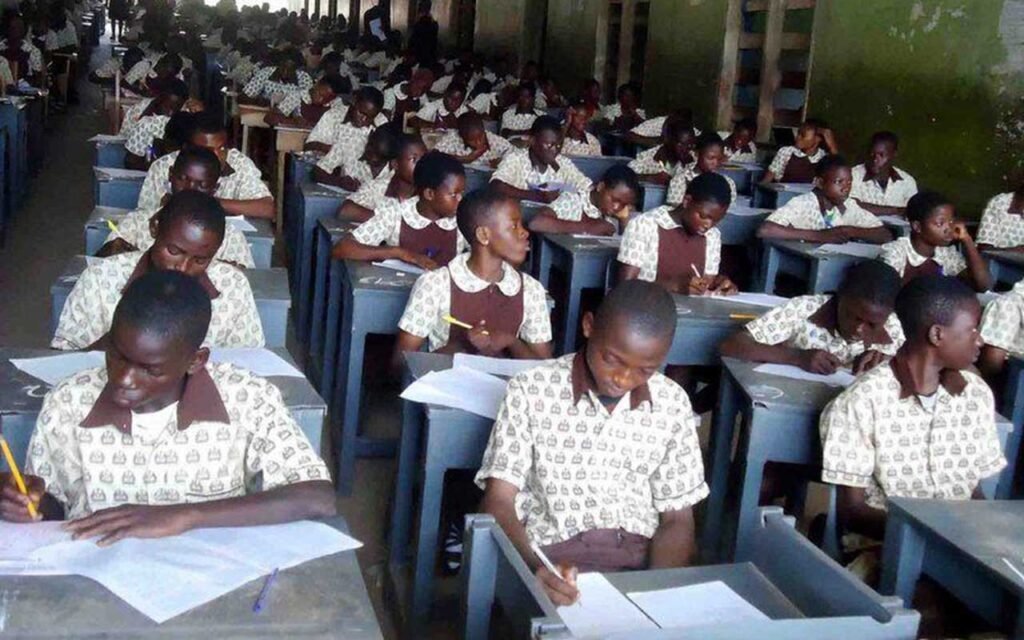

Just a fortnight into the 2025/2026 school session, Nigerian primary and secondary schools are already grappling with the formidable task of putting the newly introduced national curriculum into practice. Though the reform is ambitious and hailed by some as necessary, many educators, school administrators, and stakeholders warn that the pace and scale of implementation are proving too steep.

Across numerous public institutions, the most glaring challenge lies in delivering trade (vocational) subjects, providing relevant textbooks, and deploying trained teachers for novel disciplines. In primary schools, especially, the shift toward including digital literacy and pre-vocational content is sparking serious strain—many public schools simply don’t have the resources yet.

In secondary schools, students must now pick one practical subject—options include solar photovoltaic installation, fashion design and garment making, livestock farming, beauty and cosmetology, computer hardware and GSM repairs, or horticulture and crop production. While some well-resourced private schools are managing to equip such classes, the public sector is lagging badly behind. Many cannot access qualified teachers or tools for technology-heavy trades like solar installation or GSM repair—let alone the infrastructure required to maintain them.

Table of Contents

Voices from Schools: Hopes, Struggles, and Scepticism

In conversations with school leaders and educational experts, the picture that emerges is one of unresolved tension between ideals and messy realities.

One headteacher in a private secondary school shared that they were able to equip a fashion design unit—thanks to donations, private funding, or connections to suppliers. But in many public institutions, even sourcing sewing machines or basic kits for cosmetology is proving nearly impossible. Some principals lament that they are expected to teach high-tech subjects without the infrastructure or staff to do so credibly.

Experts addressing the issues have urged caution. They argue that curriculum rollouts of this magnitude may benefit from phased or pilot implementations rather than sweeping, country-wide starts. At a recent forum convened by the Concerned Parents and Educators Network (CPE) under the theme “Understanding the New Curriculum,” several presenters stressed the need to slow down, assess outcomes, and adapt as needed.

Taiwo Akinwalemi pointed out that Nigeria is long overdue for curriculum reform—perhaps six decades behind current global standards at some levels. But he questioned whether the timing and the expectation of full adoption from Day One might be more political than pedagogical. He asked: Have the infrastructure, capacity, and stakeholder buy-in been assessed carefully enough?

Another voice, Rhoda Odigboh, flagged systemic teacher shortages: public schools already face a shortfall of nearly 190,000 qualified personnel. She also noted that many teachers lack basic computer literacy—a huge barrier when the curriculum now embeds digital skills across disciplines. Add to that the fact that 30% of Nigerians have no Internet access, she said, and the gulf between policy and ground reality becomes stark.

Dr. Salisu Yahaya, a former education quality assurance official, emphasised that any new curriculum must be designed to interest and engage learners—especially children with disabilities. He called for more inclusive approaches, as well as greater input from private schools to ensure the reforms are responsive and workable.

Implementation Gaps: Infrastructure, Training, and Materials

The most urgent obstacles schools are running into include facilities, teacher capacity, and instructional materials:

- Infrastructure: Many schools lack basic labs, workshops, or spaces suitable for vocational subjects. There is little point in prescribing solar panel installation as a subject when no workshop exists to mount panels.

- Teacher training: Even when schools hire or assign teachers, many are unfamiliar or unqualified in the new content areas. Some teachers are reportedly still relying on rote, old curriculum methods, unable to deliver competence-based lessons in robotics, digital skills, or trade technologies.

- Learning materials and textbooks: Supply chain constraints, bureaucratic procurement delays, and budget shortfalls mean many schools are yet to receive the textbooks or supplementary resources aligned with the new curriculum.

- Equity and inclusion: Rural schools, remote areas, and under-resourced regions face the worst odds—forcing students in such places to miss out or fall behind immediately. Children with disabilities may be wholly excluded if adaptations are not planned in.

Public school administrators lament that the reform should not just be a matter of adding or subtracting subjects. It must consider readiness—who will teach, with what tools, and where. Transparency and accountability are also demanded, so implementation is monitored and adjusted as needed.

Where Next? Pilots, Partnerships, and Pragmatic Scaling

Despite the stumbling start, there is hope among reform advocates. The National Education Sector Renewal Initiatives (NESRI), under which the revised curricula fall, has supporters who insist the changes are timely and vital for national development. The Executive Secretary of the Nigerian Education Research and Development Council (NERDC), Prof. Salisu Shehu, has defended the process as inclusive and evidence-driven—seeking to dispel misinformation sweeping social media.

But at this moment, many believe the way forward should be less about grand statements and more about incremental, strategic implementation. Observers say:

- Conduct pilot runs in selected states or districts to identify pitfalls before scaling across the country.

- Focus first on the less resource-intensive disciplines, while building capacity progressively.

- Channel public–private partnerships to equip school workshops, supply materials, and support teacher development.

- Involve private schools, NGOs, community stakeholders, and local businesses to co-design and support trade subject delivery.

- Ensure monitoring, evaluation, and feedback loops so the rollout can be adjusted in real time.

- Plan for continuous teacher professional development, especially in digital, vocational, and inclusive education methods.

If done with transparency and realism, the reform has the potential to reorient Nigeria’s schools toward skills, employability, and adaptive learning. If rushed, however, it risks becoming another policy in name only—failing to transform classrooms the way it promises.

Conclusion

While the new curriculum seeks to modernise and align Nigerian education with global trends, the past two weeks have exposed significant implementation headwinds. Infrastructure deficits, capacity gaps, supply delays, and unequal resource distribution are slowing down the intended progress. The success of the reform may now depend less on the ambition of its designers and more on the coordination, adaptability, and resourcefulness of those at the coalface.

Join Our Social Media Channels:

WhatsApp: NaijaEyes

Facebook: NaijaEyes

Twitter: NaijaEyes

Instagram: NaijaEyes

TikTok: NaijaEyes

READ THE LATEST EDUCATION NEWS