As Kenya prepares to roll out its historic Senior Secondary School system in January 2026 for the first pioneer class, an education crisis is unfolding that threatens to undermine the transition. The Teachers Service Commission (TSC) has flagged a staggering shortage of 58,590 specialised teachers, leaving schools under-resourced at the very moment they should be gearing up for a new era of learning. The shortfall goes hand in hand with infrastructure deficiencies in classrooms, laboratories, libraries, digital facilities and essential student support units. This story unpacks the challenges, the risks for students, and what must happen next to avert a systemic breakdown in education quality.

Table of Contents

Historic Shift Meets Steep Obstacles

Kenya is set to welcome its first cohort of Grade 10 learners under the Competency Based Education (CBE) system in January 2026. This reform is designed to move the country beyond the old uniform curriculum and create pathways that align with students’ talents and future careers. Learners will choose between specialisations such as Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM), Arts and Sports Science, or Social Sciences, giving them more agency over their education.

Yet despite the optimism around these reforms, the reality on the ground is stark. The Teachers Service Commission, which recruits and manages educator deployment, says schools require almost 59,000 more teachers just to meet the demands of senior school subject options. Without these educators, students risk being placed in classes without qualified instructors or having their learning diluted by multi-tasked teachers who cannot provide specialist instruction.

This is not just a numerical gap but a skills gap. Many of the niche subjects central to the new curriculum, such as media technology, marine sciences, performing arts and specialised STEM fields, require teachers trained beyond general classroom instruction. With the deadline approaching, the pressure to recruit and train such teachers is mounting.

Classrooms Without Teachers and Resources

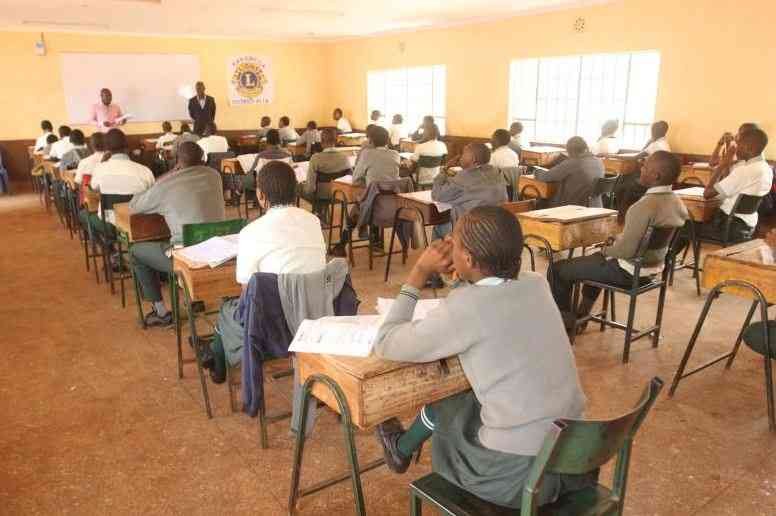

A teacher shortage of this magnitude means that classrooms risk becoming overcrowded, and the quality of education may suffer before it has a chance to flourish. Overworked teachers already face heavy workloads, with some expected to deliver lessons across multiple specialisation areas. This undermines the very purpose of the new system, which promises tailored, competency-focused learning that empowers learners with practical and critical thinking skills.

Infrastructure challenges compound the staffing deficit. Most schools lack adequate laboratories for science and technical subjects, limiting opportunities for hands-on learning. Libraries and digital learning spaces are similarly underdeveloped, weakening student exposure to research, technology and modern learning methods. In many schools, basic amenities like adequate sanitation facilities or enough classrooms are still absent, making it difficult for learners to thrive in safe, engaging environments.

The gap in science facilities, in particular, raises concerns. Laboratory work is central to understanding subjects like biology, physics and chemistry, and without proper labs, learners may be denied essential experiential learning. Teachers and experts alike have warned that one lab per school may not suffice once practical subjects are actively integrated into the senior school curriculum.

Uneven Digital Access and Learning Opportunities

In today’s world, digital literacy is no longer optional. However, the digital divide in Kenyan schools remains wide, with far too many institutions lacking computers, connectivity and training for teachers in using technology effectively. This gap not only affects subject delivery but also weakens students’ ability to engage with digital learning tools that are increasingly indispensable in higher education and the job market.

Without bridging this divide, schools in urban centres with better resources may surge ahead, while those in rural or marginalised areas lag further behind. The result could be a two-tier education system that reinforces social and economic inequalities instead of closing them.

Funding Delays and Systemic Strain

Part of the problem lies in budgeting and funding timelines. Even when resources are allocated in theory, delays in releasing funds to schools have impeded timely hiring, training and procurement of teaching and learning materials. Capitation funds, meant to support operational costs, often arrive late, leaving school administrators scrambling to balance payrolls, textbooks, classroom materials and day-to-day operations.

These bottlenecks affect not only teacher recruitment but also the ability to construct or upgrade facilities essential for senior school programmes. Laboratories, libraries, ICT centres and even basic sanitation projects remain on hold in many parts of the country, eroding parental confidence and civic support for the reforms.

Real Risks to Students and Families

For students and their families, the stakes could not be higher. Parents who have invested in textbooks, tutoring and preparation for senior school exam transitions now face the prospect of learning environments where teachers are scarce and resources thin. If learners enter senior school without competent instructors or proper facilities, their ability to compete for university placements or future careers will be jeopardised.

There is also anxiety around how schools will manage subject choices when the available staff cannot cover essential fields. Some schools may resort to assigning teachers to classes outside their expertise, while others may crowd multiple subjects into single teachers’ workloads, diluting the quality of instruction.

Steps Being Taken and What Comes Next

Kenyan authorities are not silent on these issues. In recent months, efforts have been made to recruit additional teaching staff, especially in critical subject areas. The Teachers Service Commission has opened vacancies and extended contracts for some personnel, while the government has pledged increased funding to support the rollout of the new system.

However, advocates and education experts argue that accelerated recruitment, permanent staffing structures, enhanced training programmes, and clear funding commitments are essential to close the gap. Temporary or short-term fixes may buy time, but they do not build lasting teaching capacity or the stable environments that learners deserve.

Beyond teaching positions, investment in infrastructure upgrades is crucial. Laboratories, ICT centres, libraries and even basic student rest areas should be prioritised in upcoming budgets to ensure schools are ready to deliver on the promise of the new curriculum.

What This Means for Education Reform

Kenya’s transition to Senior Secondary School represents one of the boldest shifts in the country’s education system in decades. It is a chance to redefine learning and equip young people with skills that match a rapidly evolving world. Yet, this transformation cannot succeed if schools lack the human and material resources to deliver quality education.

The teacher deficit of nearly 59,000, coupled with infrastructure shortfalls, underscores a fundamental reality: education reform must go hand in hand with investment and implementation capacity. Curriculum changes, no matter how well designed, are only as strong as the classrooms, teachers and support systems that bring them to life.

As January 2026 draws closer, all eyes will be on policymakers and education leaders to ensure that the pioneer senior school class does not walk into a system unprepared to teach, support and inspire them.

Kenya’s future hangs in the balance, and the quality of education today will define the opportunities of tomorrow. The tough choices made now will shape an entire generation’s ability to thrive in a competitive global landscape.

Join Our Social Media Channels:

WhatsApp: NaijaEyes

Facebook: NaijaEyes

Twitter: NaijaEyes

Instagram: NaijaEyes

TikTok: NaijaEyes

READ THE LATEST EDUCATION NEWS