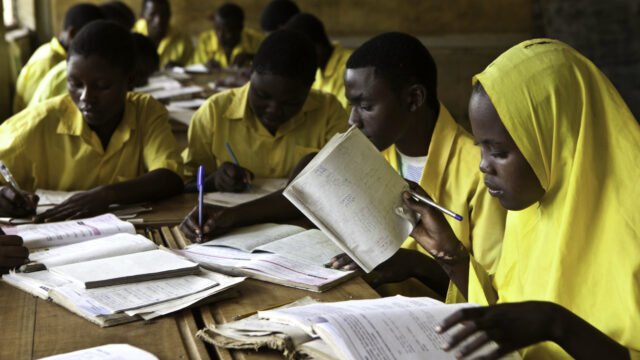

A major new report has revealed a significant shift in how Africans view their continent’s most urgent challenges, placing education at the centre of public concern. According to the latest Afrobarometer Pan-Africa Profile, education now ranks as the third-most pressing problem Africans want their governments to address. This marks a notable rise from its previous position in earlier years, reflecting growing public anxiety over the state of schooling and learning systems across the continent, as reported by IOL.

This elevation of education on the agenda is a clear signal that people are feeling the effects of persistent weaknesses in teaching, access, quality and opportunities. Africans are increasingly vocal about what they want from those in leadership, and it is shaping how national priorities are debated in capitals from Accra to Kampala, Dakar to Nairobi.

Table of Contents

Rising Concerns and Shifting Priorities

Based on interviews with 50,961 citizens across 38 African nations, the survey found that education now sits just behind health and unemployment as a priority issue that should be tackled urgently by governments. In previous survey rounds spanning 2021 and 2023, education ranked much lower on the list of public priorities.

This jump reflects a broader change in how people see their lives and futures. With economic pressures tightening household budgets, and job opportunities remaining scarce for many young people, education is increasingly being viewed as one of the most powerful levers for improving social and economic prospects. African citizens now see education not just as a service, but as a gateway to work, dignity and opportunity.

In the survey, education is now mentioned alongside concerns about the rising cost of living, infrastructure and water supply, and it sits above many other issues that have traditionally dominated policy debates. The fact that it now ranks so highly represents a shift in how ordinary Africans think about their futures and the role of their governments.

Despite its rise in importance, only about half of the respondents believe their government is doing a good job on education. Just under 49 per cent of those surveyed said their national leadership is performing “fairly well” or “very well” in delivering education services, while the remainder gave their leaders poor marks. This split verdict underscores deep public dissatisfaction with the pace and quality of reform in many countries.

Uneven Performance Across the Continent

The Afrobarometer findings show that evaluations of government performance on education vary widely from one country to another, painting a picture of uneven progress.

At one end of the spectrum, countries such as Zambia and Tanzania received high approval from citizens, with more than 80 per cent saying their governments were doing well in education. In these contexts, public confidence likely reflects targeted reforms and improvements in areas such as classroom infrastructure, teacher recruitment and curriculum updates that have begun to show results.

But in a number of other countries, public confidence in government performance is alarmingly low. In Angola, only 29 per cent of citizens think their government is performing well on education. In Chad, the figure is 28 per cent, and in Congo-Brazzaville, barely 22 per cent of respondents gave positive assessments. In Nigeria, only 24 per cent of citizens said they thought the government was doing a good job in this area.

This variation reflects deep disparities in outcomes, funding, policy focus and administrative effectiveness across the continent. In many cases, systemic problems such as outdated infrastructure, under-resourced schools, poorly paid teachers, and inadequate learning materials continue to hamper efforts to improve education.

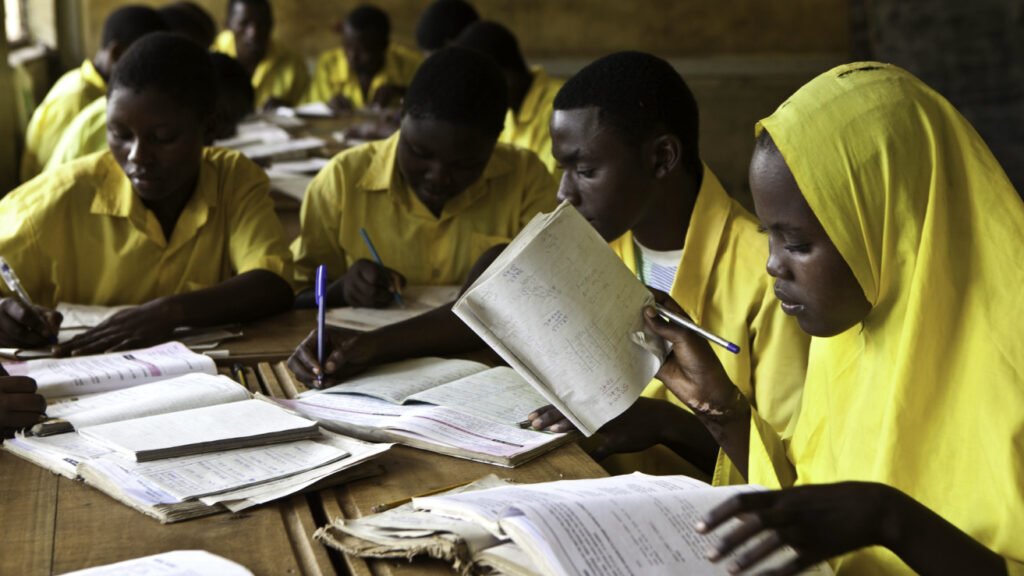

One of the most pressing issues highlighted by the survey is the gap between educational attainment among different groups. Younger Africans are generally more educated than older generations, suggesting that enrolment has increased over time. However, the gains are not shared equally. Women, rural residents and poorer citizens still lag behind, underscoring persistent inequality in access to quality schooling.

The survey also found that while relatively few respondents reported that families outright prioritise boys’ schooling over girls’, significant numbers observed serious mistreatment of girls in educational settings. Almost three in 10 people said schoolgirls often face discrimination, harassment or inappropriate conduct by teachers, pointing to urgent classroom safety and equity challenges that must be addressed if education is to serve all students fully.

Barriers to Progress and the Road Ahead

Public frustration with education outcomes is grounded in lived experiences and hard realities. Across much of Africa, insufficient funding, poorly equipped schools, high pupil-to-teacher ratios and outdated curricula have eroded confidence in formal schooling. Observers note that without stronger government commitment to sustained investment, achieving meaningful improvements will remain difficult.

Despite decades of policy commitments, many African governments have struggled to meet internationally agreed benchmarks for education funding. In 2015, UNESCO member states pledged to spend at least 4 to 6 per cent of GDP on education and to allocate 15 to 20 per cent of public expenditure to schooling. Yet in many countries this target remains elusive, limiting the resources available for basic needs like school buildings, textbooks and teacher training.

The unequal quality of education also has long-term implications for labour markets and economic growth. Without a well-educated population equipped with basic and advanced skills, countries face challenges in creating jobs, stimulating innovation, and competing in a global economy that increasingly values knowledge and technical expertise.

Another complicating factor is conflict. In places like Sudan, ongoing civil unrest has forced many schools to close, leaving millions of children without access to formal learning for thousands of days. Aid agencies warn that prolonged disruption to education can have lifelong consequences for affected children and deepen cycles of poverty and marginalisation.

Young people, in particular, see education as vital to their prospects. Yet even as enrolment has increased, many students leave school without the skills needed for meaningful employment. There is a growing gap between what schools teach and what the labour market requires, meaning that education systems must focus more on relevance, critical thinking, digital literacy and vocational skills.

For many Africans, education is now more than a policy technicality. It is a lived priority that affects daily life. Families, communities and young people themselves see it as a foundation for building secure futures and stable societies. That is why its rise on the urgent priority list of public concerns is such a powerful signal to leaders across the continent.

Building a Future Through Education

Policymakers across the continent are now under growing pressure to respond. Public demands for better schools, fairer access, stronger teacher support and safer learning environments are becoming harder to ignore. If governments want to restore public trust and strengthen their societies, education reform must be central.

Many experts argue that fixing Africa’s education problems will require a multipronged approach rooted in both policy and practice. This includes aligning education systems with economic needs, investing in teacher training, expanding infrastructure and integrating technology into classrooms to prepare students for the digital age.

International partners also have a role to play in supporting education improvements, helping governments mobilise resources, share best practices and build capacity for long-term change. The global community’s commitment to education through initiatives like the Sustainable Development Goals highlights the shared interest in ensuring that all children, regardless of where they live, have access to quality learning.

In forums from regional summits to local councils, citizens are urging leaders to treat education not as a budget line item, but as a national investment in future prosperity. The message from millions of voices across Africa is clear: education matters, and urgent action is required.

As attention continues to shift and priorities evolve, education is firmly on the public agenda. Whether governments can rise to the challenge and deliver the improvements that citizens demand will be one of the defining issues of the decade ahead.

Join Our Social Media Channels:

WhatsApp: NaijaEyes

Facebook: NaijaEyes

Twitter: NaijaEyes

Instagram: NaijaEyes

TikTok: NaijaEyes

READ THE LATEST EDUCATION NEWS