It’s a troubling picture emerging from Nigeria’s university lecture halls — despite years of study and years of service, full professors working in Nigerian tertiary institutions are earning wages that barely register on the continental scale. A recent comparative review has revealed that the average monthly pay for a professor in Nigeria hovers around US $366 (about ₦550,000).

Contrast that with the earnings of roughly US $4,800 per month for their counterparts in South Africa. For Ghana, the monthly figure is about US $720.72, for Lesotho, US $834, and for Kenya, US $1,316.

But this is not just about money. Many academics warn that this wage gap is undermining morale, contributing to a braindrain, and threatening the quality of university education across Nigeria.

Table of Contents

The Human Cost: Brain Drain, Strain and Frustration

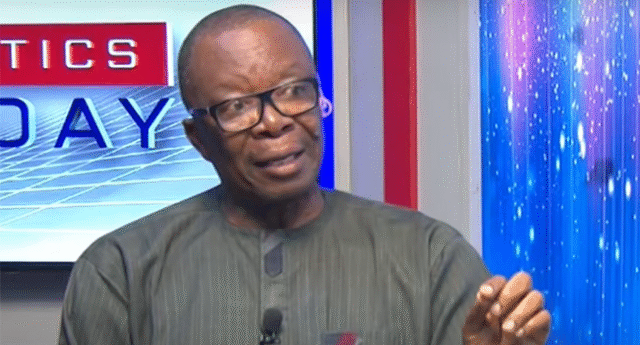

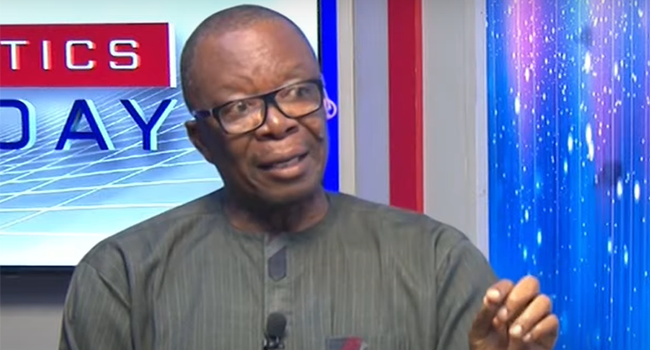

Professors at home in Nigeria say the situation is demoralising. According to the national union, the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU), it is unsustainable for highly educated scholars to accept wages that place them among the worst-paid professionals in Africa.

One chairperson from Ladoke Akintola University of Technology (LAUTECH) described how, at the peak of their career, professors now find it hard to keep up with rising costs. “Imagine someone who has reached professorial rank earning less than US $500,” he said.

Beyond the personal frustration, the wider implications are stark. Losing experienced lecturers to better-paid opportunities abroad or in industry reduces institutional memory and weakens departments. ASUU warns that universities may begin to resemble the post-independence era when many lecturers, especially expatriates, were leaving.

There’s also the research aspect: academics report that if they cannot cope with basic living expenses, their capacity to undertake meaningful research or publish internationally is seriously constrained. A deteriorating welfare environment is not simply a comfort issue—it is a productivity and quality issue.

What Explains the Pay Gap and Why It Matters

Several factors come together to create this pay disparity. Firstly, currency devaluation plays a significant role: in Nigeria, the naira’s weakness means that even nominal salary increases translate to substantially less in dollar terms.

Secondly, the underfunding of public universities remains a chronic issue. ASUU has called for a thorough review of the 2009 agreement between the union and the federal government, arguing that funding for research, infrastructure, and salaries has lagged.

Thirdly, when a country fails to pay academics in a way that reflects their value, the consequences ripple outward. For one, students may be taught by less motivated or less experienced staff. For another, the incentive to remain in the academic profession diminishes, resulting in talent shifting into other sectors or leaving the country altogether.

The larger stakes are national. If tertiary institutions degrade in standard or lose senior faculty, the pipeline feeding Nigeria’s doctors, engineers, educators and scientists gets thinner. In effect, what appears to be a salary negotiation becomes a question of national development.

What Needs to Be Done — and Why Now

There is urgency here. The system cannot afford to drift while the best minds opt out or move on. ASUU is clear: if the government does not act within an agreed window, strike action may follow.

Key actions include:

- A comprehensive salary review for professors and lecturers, benchmarked against African peers and adjusted for the cost of living.

- Increased funding for public universities—not just for salaries but for infrastructure, research grants, and international collaboration.

- A strategic retention policy for senior academics, including incentives for research output, global partnerships and mentoring younger faculty.

- Transparent and timely implementation of agreements between the union and government, so that arrears are cleared and confidence restored.

As one academic remarked, it is no longer acceptable for Nigerian professors to earn less than US $500 while doing the same job, in the same region, as colleagues who enjoy far higher remuneration.

In a sector as vital as higher education, remuneration isn’t just a cost line—it is a signal. It signals how a country values knowledge, scholarship and the future of its youth. Nigeria’s universities are pivotal engines of growth, yet if those engines are poorly paid, they risk stalling.

It’s high time for policymakers, university management and scholars themselves to ask: do we wish for a tertiary-education system that competes on the continent—or one that falls further behind?

Conclusion

Nigerian professors are earning dramatically less than their African peers—a gap of more than tenfold in some cases. This pay divide is undermining morale, precipitating brain drain and putting the quality of tertiary education at fault line. With clear strategies and urgent action, the drift can be reversed. Without it, the country risks compromising not just its universities, but its future.

Join Our Social Media Channels:

WhatsApp: NaijaEyes

Facebook: NaijaEyes

Twitter: NaijaEyes

Instagram: NaijaEyes

TikTok: NaijaEyes

READ THE LATEST EDUCATION NEWS