Recently, Nigeria’s Federal Ministry of Education introduced a “future-ready” curriculum, spanning from early primary school through to senior secondary and technical college levels. On paper, this reform is impressively ambitious. Primary pupils will see lighter timetables, history restored as a core subject, and technical colleges pushed to update what and how they teach. At secondary level, JSS1 pupils must now take at least one trade subject—such as solar installation, garment making, livestock farming, cosmetology, GSM/computer repair, or horticulture—while digital technologies, coding, robotics and artificial intelligence are being introduced as core. The goal: to ensure a child leaving secondary school is not just literate, but employable and digitally literate.

Table of Contents

The Reality Check: What Our Classrooms Demand

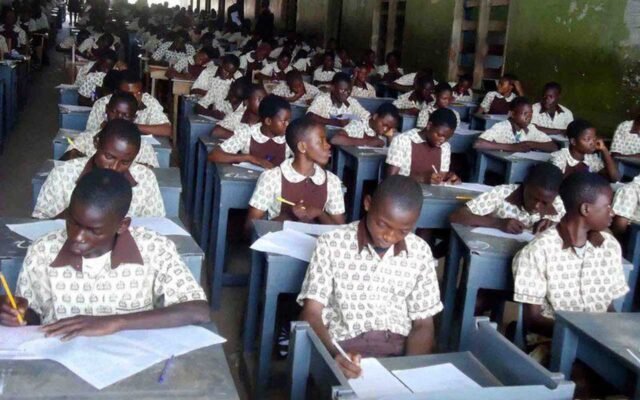

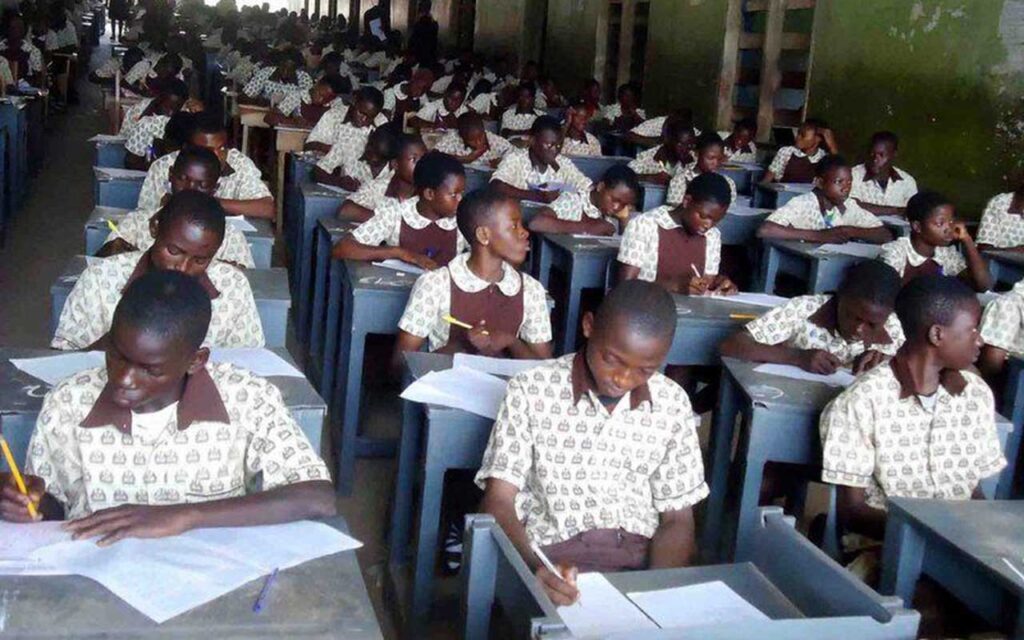

Ambition alone, however, will not suffice. Nigeria has long announced grand plans for its education sector; what we often lack is the capacity to deliver. This reform brings three essential pillars into sharp focus: teachers, infrastructure/workshops, and appropriate assessments.

- Teachers: Are there enough qualified instructors with real experience in trade and digital subjects? Many schools do not have teachers who can supervise practical work—wiring, stitching, solar panel installation, etc. Without capable and confident teachers, the “skills” components reduce to academic theory.

- Infrastructure and Workshops: For trade and technical subjects to be meaningful, there must be functional workshops, electricity supply, equipment, and space. In many Nigerian schools, light bulbs themselves cannot be guaranteed. How then, for example, will a school teach solar installation when light and power are irregular?

- Assessment Systems: If examinations continue to be theory-centred, schools will focus on textbook content that appears on tests, neglecting hands-on skills. National and state exam bodies—WAEC, NECO, NABTEB—must produce specimen papers aligned with the new subjects, not only in theory but in practice. Without this, schools will revert to rote learning modes.

Uneven Readiness: States, Resources, and Accountability

Nigeria’s federal structure means that while the reform is national, implementation will vary widely among states. Wealthier states may find it easier to raise resources, train teachers, partner with industries, and build workshops. But states with limited budgets will struggle.

Some encouraging steps are already underway: the Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC) is preparing states; the Nigerian Educational Research and Development Council (NERDC) is revising materials; examination bodies have promised to align with the new curriculum. However, the success of the reform hinges on transparency and accountability. Stakeholders—teachers, parents, civil society—must ask the tough questions:

- How many trade teachers are already trained?

- Which schools have functional workshops?

- Do all schools have access to reliable electricity and equipment?

- When will specimen papers be released for subjects like solar installation, AI and robotics?

Primary schools must update materials and prepare teachers, especially now that history is reinstated. Technical colleges require new programmes and equipment so that trade education is more than labels—it must be real, skill-based education. And universities must adjust teacher-training to ensure that the teachers of tomorrow can deliver this curriculum.

Why This Reform Matters—and What’s at Stake

At stake is more than academic policy. This new curriculum carries hopes—hope that students will finish JSS1 or senior secondary school not only able to read, write, and calculate, but also able to weld, wire a circuit, fix a phone, sew a garment, or grow food. Such skills can affect livelihoods, employability, self-esteem, and national economic prospects.

If it succeeds, education will feel tangible to children. They will see relevance in what they learn. If, however, what they take away are only theory passages and unpractised trade names, the reform risks collapsing into cynicism. “Future-ready” might become “future-forgotten”—a policy whose promise faded long before its delivery.

Conclusion

This curriculum reform is Nigeria’s chance to bridge the gap between policy and practice, between promise and delivery. We must measure its success not by what is written in government releases, but by what happens in JSS1 classrooms across the country. Do students in remote states have access to tools, teachers, and real workshops? Are exam bodies assessing hands-on work as well as theory? Are primary schools equipped, technical colleges resourced, and teachers trained?

Civil society, parents, teachers, and governments at every level must work together. Because for this vision to become reality, Nigeria’s classrooms must not just announce reform—they must live it.

Join Our Social Media Channels:

WhatsApp: NaijaEyes

Facebook: NaijaEyes

Twitter: NaijaEyes

Instagram: NaijaEyes

TikTok: NaijaEyes

READ THE LATEST EDUCATION NEWS