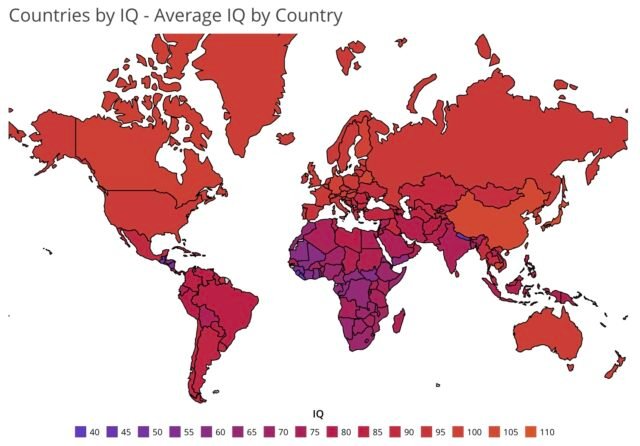

The latest insights into national cognitive metrics have surfaced, revealing stark disparities in average IQ scores across the globe. As environmental, social, and historical factors converge, certain nations consistently rank at the bottom of these assessments. In 2025, the ten countries with the lowest recorded average IQs are: Nepal, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guatemala, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Nicaragua, Guinea, Ivory Coast, and Ghana. These results—while controversial—serve as a dramatic illustration of global inequality, prompting a closer look at the structural conditions fueling these trends.

Countries With Lowest IQ

1. Nepal – Average IQ: 42.99

Topping the list, Nepal’s reported average IQ of 42.99 is notably the lowest in the world in 2025. This Himalayan nation faces persisting challenges such as geographic isolation, widespread rural poverty, and chronic undernutrition, all of which hamper early childhood brain development and education access.

Despite governmental efforts, many remote communities remain cut off from quality schooling, trained teachers, and essential health services. Malnutrition—particularly in the earliest years—also exacts a heavy toll. According to health data, subtle deficits in nutrition during the first 1,000 days of life correlate strongly with long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Critics point out significant measurement bias in ranking Nepal at the bottom. Standardised IQ tests are rooted in Western frameworks, potentially disadvantaging local populations in Nepal who are more tuned to oral traditions, indigenous languages, and context-specific reasoning.

2. Liberia & 3. Sierra Leone – Average IQ: ~45.07

Tied closely in second place with averages around 45.07, Liberia and Sierra Leone rank as the two lowest-scoring countries in West Africa. Both nations have endured devastating civil wars (Liberia: 1989–2003; Sierra Leone: 1991–2002), followed by health crises like Ebola that tore through fragile healthcare infrastructures.

These conflicts dismantled school systems and left generations without basic education. Lingering malnutrition, limited access to medical care, and emotional trauma continue to hinder cognitive development. Research demonstrates that child health conditions—especially chronic infection—are strong predictors of lower average IQ scores at the national level.

Yet, the narrative of national ranking obscures a more complex reality: international aid and local NGOs have launched ambitious interventions, including mobile schooling and nutrition programs, aiming to reverse long-standing disadvantages.

4. Guatemala – Average IQ: 47.72

Guatemala, the lowest-ranking country in Central America with an average IQ of 47.72, reveals the high cost of linguistic and cultural marginalization.

Nearly half of Guatemalan children under five suffer from chronic malnutrition. Add to this the fact that nearly 40% of the population identifies as Indigenous—many of whom learn Spanish as a second language—and it becomes clear why IQ tests, typically administered in Spanish, may severely underrepresent intellectual ability among rural learners.

Recent reforms aim to bridge the gap by expanding bicultural education, culturally-adapted assessments, and investment in rural teacher training. Still, entrenched socio-economic challenges remain a persistent barrier.

5. Cape Verde & 6. The Gambia – Average IQ: 52.50

Tied at 52.50, Cape Verde and The Gambia appear at the next two lowest spots. While Cape Verde is a relatively stable island democracy, it grapples with scarce resources, geographic isolation, and limited healthcare infrastructure, especially across its archipelago.

In The Gambia, population density and poverty coincide with under-resourced schools and insufficient maternal–child health interventions. These issues are amplified by recurrent food insecurity that interrupts children’s educational trajectories.

Both countries share geographic and economic challenges that make reliable data on cognitive outcomes difficult to collect and contextualize, questioning whether IQ scores fully capture lived reality.

7. Nicaragua – Average IQ: 52.68

Nicaragua’s average IQ of 52.68 reflects its turbulent socio-political environment. Ongoing political instability since 2018 has disrupted education systems—many teachers were dismissed, and students were displaced. These interruptions overlap with persistent poverty (despite literacy rates improving above 80%) and widespread undernutrition that stifles both mental and physical growth.

Conversely, Nicaragua has made progress in rural health outreach and micronutrient supplementation. International support has boosted rural school enrollment and teacher training. Yet volatility remains a constant factor, limiting long-term gains.

8. Guinea – Average IQ: 52.69

With an IQ of 52.69, Guinea stands amid the challenges of political instability, limited educational infrastructure, and high disease burden. Sub-Saharan West Africa remains one of the regions where data collection has been most difficult—sampling is sparse, and standardised IQ testing is rare.

Epidemiological studies link poor cognitive outcomes with prevalent infectious diseases and environmental factors—particularly malaria and intestinal parasites—though strategies are underway to improve vaccination, water quality, and primary school access.

9. Ivory Coast – Average IQ: 53.48

Ivory Coast, with an IQ of 53.48, shares many patterns with Ghana, its neighbour. Though it benefits from higher economic growth, large segments of the population—especially in rural areas—lack quality health and education services.

Lingering effects of civil conflict (2002–2011) still impact school infrastructure, teacher attrition, and community stability. Nutrition programs and school feeding have expanded recently, but equitable access remains uneven.

10. Ghana – Average IQ: 58.16

Ranking tenth-lowest with 58.16, Ghana illustrates a paradox: regional stability and democratic governance alongside uneven developmental outcomes.

Urban centres—such as Accra and Kumasi—boast good schools and healthcare. However, the rural north lags significantly in developmental indices. Malaria, food insecurity, and educational resource allocation create cognitive gaps between regions.

Understanding the Broader Context

The Pitfalls of IQ Ranking

These global IQ assessments are rooted in data compiled through varying methodologies—some including Richard Lynn and Tatu Vanhanen’s controversial work, others derived from small online test samples. Their conclusions have been widely challenged for methodological inconsistencies, biased sampling, and cultural platform effects.

One prominent critique, from Eppig, Fincher & Thornhill, proposes that national infectious disease burden—rather than genetics or IQ per se—explains much of the variance in cognitive scores. It suggests that under-functioning health systems directly impact brain development, and that cognitive disparities shrink when disease control improves.

The Flynn Effect & IQ Evolution

Historically, global IQ scores rose by an average of 3 points per decade through the 20th century—a phenomenon known as the Flynn effect. These gains were largely driven by improvements in education, health, and nutrition, but many developed nations are now plateauing or declining, highlighting shifting societal environments.

Whether these lower-ranking countries are experiencing a Flynn effect remains unclear; the data is too fragmented for stable longitudinal tracking.

Why These Figures Matter

Why It’s Important

- Signal for Policy Priorities

IQ ranking signals often correlate with weak early childhood nutrition, educational deficits, disease exposure, and socioeconomic fragility. These signals can guide international aid and domestic resource allocation. - Highlighting Equity Gaps

Countries like Guatemala and Ghana show how regional, linguistic, and societal disparities—particularly affecting Indigenous populations—can distort national metrics unless addressed. - Championing Contextual Intelligence

IQ tests are limited—they do not capture emotional, social, or creative intelligence. Researchers emphasize cognitive diversity and cultural relevance rather than rigid ranking.

What Can Shift the Landscape

- Robust Early Childhood Investment

Nutrition support, early education, and disease prevention in infancy yield lifelong cognitive dividends. - Inclusive Schooling and Teacher Development

Girls’, rural, and minority education initiatives must be prioritised with locally-relevant curricula, multilingual instruction, and sustained public investment. - Universal Health Access

Controlling infectious disease burdens—especially maternal and childhood diseases—has direct cognitive benefits. - Data-Informed Governance

Measuring what matters: equity, multilingual outcomes, and regional progress should complement national averages to inform policies robustly.

Reframing “Low IQ” as Structural Failures

It’s crucial to understand that an average national IQ below 60 is neither an inherent trait nor a genetic verdict—it’s a structural symptom. Factors such as conflict, underfunded infrastructure, health crises, discrimination, and environmental neglect contribute far more than genetics ever could.

Moreover, scores themselves are a limited measure. As psycho-social models of intelligence expand, categorising whole populations by narrow benchmarks becomes less justifiable. Diversity in cognition—social, creative, survival-based, and emotional—is lost in numeric summaries.

Looking Ahead: Towards Equity-Aligned Metrics

A more humane, policy-relevant model would integrate:

- Child Development Indices, including stunting rates, early grade reading proficiency, and school completion.

- Health Integration Metrics covering vaccination rates, access to clean water, and disease burden per region.

- Educational Equity Audits track bilingual education availability, teacher density by district, and gender parity.

- Socioeconomic Inclusion Measures such as poverty rates, rural electrification, and internet access.

These factors create a composite picture more actionable and reflective than median IQ alone.

Final Thoughts

The 2025 list of countries with the lowest IQ—led by Nepal (42.99), Liberia, Sierra Leone (both ~45), Guatemala (~47.7), Cape Verde & The Gambia (~52.5), Nicaragua (~52.7), Guinea (~52.7), Ivory Coast (~53.5), and Ghana (~58.2)—is not an indictment of potential. It is a stark CCR: a Cognitive Capital Report-card pointing to where national and international systems are failing.

Behind each number lies a real child missing a meal, a rural village without a school, or a community left vulnerable to preventable disease. These aren’t scores assigned—they’re symptoms revealing where targeted, sustained investment can transform generations.

The headline “countries with lowest IQ 2025” should, however, read more as a rallying cry. A call—backed by data and evidence—to reshape health policy, education reform, and economic equity in nations where potential remains desperately untapped.

Join Our Social Media Channels:

WhatsApp: NaijaEyes

Facebook: NaijaEyes

Twitter: NaijaEyes

Instagram: NaijaEyes

TikTok: NaijaEyes

READ THE LATEST ENTERTAINMENT NEWS