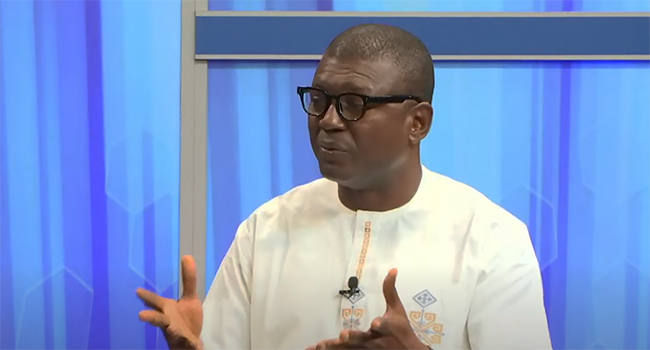

Benue State University of Agriculture, Science and Technology (BSUAST) Vice-Chancellor and Executive Director of the Centre for Food Safety and Agricultural Research (CEFSAR), Professor Qrisstuberg Amua, has issued a compelling critique of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), characterising them as instruments of disguised economic colonisation. In a televised interview on August 2, 2025, he challenged prevailing narratives promoted by regulatory agencies and multinational seed corporations.

Table of Contents

Shaming the Narrative on GMOs

Professor Amua responded emphatically to remarks by Dr. Yemisi Asagbra, Director‑General of Nigeria’s National Biosafety Management Agency (NBMA), who recently suggested that rural agriculture alone would not sustain Nigeria—a statement Amua labelled as “shameful.” He asserted that the implication that Nigeria cannot manage food production without GMO seeds is misleading and undermines national self-reliance.

Amua, whose roots are in Nigeria’s agricultural heartland of Benue State, emphasised that the region is abundantly capable of feeding the nation. “A lot of fruits—mangoes, oranges, vegetables—are going to waste due to lack of preservation infrastructure, not lack of seeds,” he explained. According to him, the real problem lies in poor post‑harvest technologies, weak economic structures, and minimal value‑addition, not seed genetics.

Food Insecurity: A Matter of Economics, Not Seeds

Drawing attention to systemic issues, Amua argued that Nigeria’s food insecurity is largely rooted in economic poverty and inadequate infrastructure. Even where arable land and labour are plentiful, the absence of storage, processing, and preservation systems leads to massive post‑harvest losses. “So it is not the truth. GMOs are a market strategy, a commercial strategy to erode national sovereignty,” he declared.

He further underscored that our farming traditions and agronomic expertise have been sidelined in favour of quick-fix seed technologies from foreign corporations. Importantly, he warned that blindly importing patented seeds from multinational firms like Monsanto, Bayer, or Syngenta risks surrendering agricultural control to external entities.

Institutional Capture and Geopolitical Interests

Professor Amua voiced deep concern over what he described as institutional capture. He warned that regulatory structures like the NBMA and the Nigerian Seed Council are susceptible to influence by commercial entities pushing patented GMO seeds. “The companies behind this are known for institutional influence,” he said, noting media visibility but lack of local ownership and oversight.

He also questioned the narrative framing that rural agriculture is no longer viable without genetic alteration. “If we continue to push this narrative, we position Nigeria to fail before we even begin,” he cautioned.

Can Nigeria Develop GMO Tech?

When asked whether Nigeria should negotiate for the local production of GMO seeds, Amua did not close the door completely, but raised critical questions. “Under whose patent are these seeds? Who controls the technology?” he asked. He revealed a glaring gap: for more than a decade, even sophisticated biotechnology labs in Port Harcourt remain unused—equipment boxed, personnel untrained, capacity undeveloped. As a result, Nigeria lacks the infrastructure and technical expertise to safely create or regulate GMO seeds.

Amua acknowledged it may not be wrong to pursue indigenous GMO development, but only if Nigeria possesses the capacity and retains full ownership of the patents and technology.

Labelling GMOs: Impractical in the Nigerian Reality

Dr. Asagbra suggested that mandatory labelling of GMO‑derived foods might offer consumers a choice. Professor Amua was dismissive: given Nigeria’s informal food markets, labelling is effectively meaningless. He illustrated how Nigerian street vendors selling bean cakes, akara, pap, and local staples would have no means or motivation to identify GMO ingredients in their goods.

He argued that food labelling regulations are largely unenforceable in Nigeria, especially when the population is food insecure, displaced by conflict, or living in IDP camps. “Hungry people don’t ask questions; they eat what’s available,” he observed.

The Human Cost: Smallholder Farmers and Vulnerable Communities

Beyond the technological and geopolitical dimensions, Professor Amua spoke passionately about the people at stake. He warned that pushing for GMO adoption favours large-scale commercial agriculture at the expense of millions of smallholder farmers. “We risk displacing farmers, deepening inequality, and exposing vulnerable populations to unregulated consumption of proprietary seeds,” he stated.

Amua urged policymakers to prioritise inclusive agrarian models: those that uplift small-scale farmers, use local crop varieties, and harness Nigeria’s vast youth demographic (Nigeria’s median age is 19) in value-added, climate-smart agriculture. This, he says, would strengthen food sovereignty and create sustainable livelihoods.

Charting an Alternative Path Forward

Drawing a roadmap from grassroots to national policy, Professor Amua outlined a three‑pronged vision:

- Revive Traditional Agronomy: Invest in agronomic education and best practices to maximise yields from native seeds.

- Build Infrastructure: Develop post‑harvest facilities, processing centres, and storage technologies across agricultural regions.

- Promote Local Ownership: Foster indigenous research capabilities, train scientists, and prioritise patent control in seed development.

He placed responsibility both on institutions and political leaders to harness Nigeria’s untapped arable land and youthful workforce, transforming them into engines of sustainable productivity.

Conclusion

In a period when corporations and global narratives are reshaping agriculture across the globe, Professor Amua’s message is clear: GMOs are disguised economic colonisation tools, not benign scientific progress. He warns Nigeria risks surrendering sovereignty, disempowering farmers, and undermining food autonomy if it ignores the economic and political dimensions of seed importation.

Rather than accepting the dominant discourse—that only patented biotechnology can feed future generations—Amua advocates for bold investments in local infrastructure, agronomic training, and policy reform tailored to Nigeria’s context.

Summary of Key Points

| Theme | Key Message |

|---|---|

| Shaming the GMO Narrative | Big‑agriculture bias may marginalise millions of local farmers |

| Agricultural Reality | Food loss stems from weak infrastructure, not seed inadequacies |

| Economic Sovereignty | Patented seeds threaten local control and autonomy |

| Institutional Influence | Capture by multinational firms undermines regulation |

| Local Capacity Deficit | Nigeria currently lacks the ability to develop patented seeds |

| Labelling Limitations | Informal markets make GMO labelling ineffective |

| Smallholder Risks | Big‑agriculture bias may marginalize millions of local farmers |

| Alternative Strategy | Strengthen local skills, seed systems, and agro‑infrastructure |

Professor Amua frames Genetically Modified Organisms not as a solution, but as strategic levers employed by economic powers to undermine national agricultural independence. He urges a return to self‑reliance, local capacity-building, and the prioritisation of Nigeria’s own agronomic heritage.

By focusing on the key phrase “GMOs disguised economic colonisation tools”, this article aims to provide standout visibility on this critical debate, centring sovereignty, science, and social justice in Nigeria’s agricultural discourse.

Join Our Social Media Channels:

WhatsApp: NaijaEyes

Facebook: NaijaEyes

Twitter: NaijaEyes

Instagram: NaijaEyes

TikTok: NaijaEyes

![Mr Macaroni Drops Blistering Remark: ‘APC Filled with Most Corrupt People’ as He Slams Tinubu’s Controversial Pardon for Criminals=]] Mr Macaroni](https://naijaeyesblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Mr-Macaroni-1-1-180x135.avif)

![Chaos Erupts in Abuja Hotel as BBNaija Star Phyna Sparks Fierce Scene Over Alleged N200,000 Dispute [VIDEO] Phyna](https://naijaeyesblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/A-Picture-of-Phyna-BBNaija-180x135.jpg)